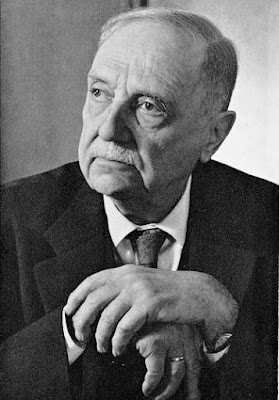

Rudolf Bultmann: theologian of Advent

As most who read this blog know, my dissertation is technically on Barth and Bultmann, but my primary interest is in reinterpreting Bultmann and reviving him for a new generation of theology. One of the many benefits of this project has been the chance to read Bultmann’s sermons, especially those that were published posthumously in 1984 in the collection, Das verkündigte Wort. Nine of the pieces in this work were written for Advent. They confirm in a striking and profound way the fact that Bultmann is the theologian of Advent par excellence. His key verse is John 1.14: “And the Word became flesh and lived among us...” For Bultmann, all theology is christology, and christology is about the paradoxical identity of divinity and humanity in this concrete historical event.

One of the sermons, “Der Sinn des Weihnachtsfestes,” was delivered in Marburg on December 17, 1926. I have translated a section from the end of the sermon that I have found immensely helpful in understanding Bultmann. As with all his Christmas writings, it is an example of his theological mind operating at the highest level and on a topic of profound concern to him. (Please forgive the woodenness of the translation.)

The message of Christmas is: there is a second beginning; that event, “the Word became flesh,” is this beginning, in which love became an actuality. How can love be a possibility for us, become an actuality for us, if we come from hate? One way only: by the fact that we are loved. How can we become new, start a new beginning, get away from ourselves? One way only: through love that forgives. ...

We are confronted by the choice whether this beginning will be our beginning. It is not an event that has created objective world-historical values which are bestowed on us without our choosing, that is, without faith. It is not an event that has led to a world-historical occurrence, in whose so-called blessings we all readily participate. But instead it is an event that, as a beginning, is always ever a beginning; it was not once a beginning that has now long since been built over, indeed, rendered obsolete by means of a developmental process. In the pagan idea that God is always born anew, in the childish thought that the Christ-child is always a child, lies a meaningful clue. ... Precisely this is the reason that we celebrate his birth, the Christ-child; because it brings to expression the fact that we do not fancy him according to human standards of what is great and impressive, but rather that we hold in earnest to the claim: “The Word made flesh.” Of course, when we say, “always beginning,” we are not talking about an eternal becoming-human of the divine in humanity, but instead we speak of that one event that has divided history, of that human being in whom God’s love appeared as an actuality. When we say, “always beginning,” we thus mean: this event always demands our decision. We have to choose whether it will be a beginning for us.

In truth, this event, which always wants to be the beginning for us, is in fact always the beginning for us, whether we want it to be or not. We choose always only in which sense it will be the beginning for us. For ever since this event took place, all history has been marked by it. The one who chooses it has chosen life, and the one who spurns it has spurned nothing less than life itself; that person has chosen death. Each person has chosen. One cannot ignore this beginning, and even to ignore it is to take a position; the one who spurns love remains in hate.

And finally, once again: “The Word became flesh,” God became a human being. It’s not about the miraculous transformation of some cosmic substance, but rather the fact that through the birth of a human being history has been decisively determined. It’s also not about the fact that we have sensed God’s grace in special matters and special experiences as something extra, but rather the fact that in the person of Jesus Christ God’s grace and actuality have appeared and marked our history. As flesh, as human beings, we belong to the history whose beginning he is. If we believe in him, this means that we believe that these occurrences of everyday life, these doings and sufferings, these givings and receivings, in which we stand as human beings, can and should be stamped with the mark of love. In view of that beginning, this life should be guided by faith in the love that surrounds us with forgiveness—in the love whose word, if only that one great word is heard, can become everything. But, of course, that is only if we ourselves become such a word of love, that is, if we love. Since one can only love as one who is loved, to whom love has been given, so one can also only receive love if one accepts it as the power to love in obedience.

“In this is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son as the reconciliation for our sins. Beloved, since God therefore loved us, we also should love one another.”

Rudolf Bultmann, Das verkündigte Wort: Predigten, Andachten, Ansprachen 1906-1941, ed. Erich Grässer and Martin Evang (Tübingen: Mohr, 1984), 237-38.

Comments